You are invited to not pray!

That’s right, you read the title correctly. I am inviting you to not pray. Come to synagogue tomorrow morning, sit for an hour, or two, or three, and don’t pray. I am allowed to say that because, frankly, I have no idea what the English words “to pray” mean. The meaning of the words, I believe, will necessarily change depending on what is our definition of God. Implicit in the word “prayer” is some recognition that we are engaging in an effort to connect to something beyond ourselves, whether that something is above us, beyond us or within us. Are we asking for something, actually expecting a response? Are we seeking the granting of a wish? Are we hoping to gain a perspective that puts our lives into a context of something greater, thereby either maximizing or minimizing our significance, our achievements, or even our wrongdoings? Prayer is not necessarily an act of petition, supplication or thanksgiving. It may be all these things, it may be none of these things.

In our Siddur Lev Shalem, the new prayerbook published by the Rabbinical Assembly which we introduced to the congregation two weeks ago, the phrase Barukh Atah Adonai, commonly translated as “Praised are You, Lord,” is intentionally left untranslated. In the English text, the phrase appears simply as Barukh Atah Adonai. I love the affirmation of the idea that the words cannot be translated easily, if at all. How do we approach sacred purpose? How do we express shared values and shared search for meaning? How do we establish a space for safe vulnerability? How do we sing in gratitude for our freedom and in lament of those things that still enslave us? How do we find inspiration and comfort in the company of others who are as imperfect and broken as we are? That which we can’t translate into words is left to the service of the heart.

The beauty of our new siddur is found in its acknowledgment that there is no single way to pray. The book is an invitation to a dialogue with God, certainly, but it is also an invitation to meditation, to study, to quiet contemplation, to communal song. It is as modern, creative, and untraditional as we need our expression of faith to be. It is as ancient, as set and as traditional as we need our expression of faith to be. It is an invitation to explore our desire to connect emotionally, intellectually and socially to purpose, values, tradition, shared history and shared mission.

Jewish tefillah–self-examination–is time set aside from the mundane distractions in our lives. The siddur serves as the open doorway to that time–time for perspective, time for growth. Join us tomorrow morning for an hour or two or three. Join us for you. Join us to learn more about this new magnificent resource and our own personal searches for meaning. Join us to sing, learn, connect, and be. Join us, you know, to pray.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Craig Scheff

Choosing Not to Listen

18,000 of us converged on Washington for three days: Jews of every stream, nationality and political persuasion; Jews who are high school kids, college students, Holocaust survivors, rabbis. Also gathering were delegates who are Hispanic, people of color, Evangelical Christians, main line Christians, politicians. We came to AIPAC’s Policy Conference because all of us are supporters of the Israel–America alliance.

Imagine it: 18,000 filling the hallways and meeting rooms of the Washington Convention Center. 18,000 dramatically filling the arena of the Verizon Center to hear Vice President Biden, Israel’s Prime Minister Bibi Netanyahu, and most of the candidates currently running for president.

The person sitting next to me in a session about the refugee crisis in the Middle East may not have agreed with me about most things, but we are both similarly committed to Israel’s right to exist as a free, secure, Democratic nation. The people on either side of me during the campaign speeches may be voting differently than me, but we all agree on the necessity of friendship between Israel and America. The rabbis at my table listening to Natan Sharansky speak about the rise of anti-Semitism and the insidiousness of BDS may have different politics from mine, but we all agree that Israel is as necessary to American security as America is to Israel’s.

As always at AIPAC events, I listened to thinkers and politicians from the left and the right. Stav Shafir, Member of Knesset and one of the founders of the Israeli social justice protest (Mechaat Tzedek Hevrati), shared her idealistic vision for a progressive and optimistic future for Israel.

Author of My Promised Land, Ari Shavit criticized the current government in Israel, saying that Religious Zionists are endangering our home and Ultra-Orthodox Jews are endangering our religion. From the other side of ideology, Pulitzer Prize winner Bret Stephens shared his vision of security for Israel. Writer for The Atlantic, Jeffrey Goldberg, discussed his critique of the Obama administration’s Middle East policy.

The voices were a cacophony of harmonious disagreement. For me, this fact is the power of AIPAC.

As delegates, we listen respectfully to learn about a variety of perspectives and make up our own minds. Learning from the diversity of thought at AIPAC has enhanced my understanding of one of the most complicated situations in our world today. Over time, I have definitely changed my mind about certain things. But never have I wavered from the belief that when Israel and America are strong, the world is more stable.

This year for the first time in nine AIPAC Policy Conferences, I chose NOT to listen to one of AIPAC’s guests. I did not stage a protest or a walkout. Together with Rabbi Scheff, our intern Paula Rose, and fifty other rabbis, I chose to study Torah rather than to be in the arena when Donald Trump spoke. We gathered in a restaurant inside the center to hear words of Torah and sing Olam Chesed Yibaneh, (with loving kindness the world is built).

I do not judge the choices that others made with regard to Mr. Trump’s speech. Some walked out but did not gather with others, other delegates stayed in to listen to his words. Some maintained silence and others clapped politely. Some clapped enthusiastically. I acted according to my own conscience and not in anyone else’s name. I acted, but not in order to judge others.

I understood from the outset that AIPAC’s mission requires all presidential candidates to be invited and I support the invitation to Mr. Trump among all of the presidential candidates. But I could not in good conscience listen to a person whose rhetoric has been anchored in racism, Islamophobia, xenophobia, misogyny and calls to violence. Judaism’s most fundamental value teaches us that all people are worthy of respect because we are created in God’s image. As a rabbi and as a Jew, I felt a moral obligation NOT to listen, to refrain from lending legitimacy to a candidate for the highest office in America who engages in hateful speech.

Over my 10 years of participation in AIPAC, I have been taught to welcome all speakers with dignity and respect. No one boos or heckles a guest of AIPAC. We clap if we agree and we are quiet if we disagree. I have listened to policy with which I agreed and sharply disagreed. I have always listened. At Policy Conference 2016 I chose not to listen.

In so doing, I pray that my fellow rabbis and I made space for words of loving kindness.

I pray that words of loving kindness will disarm words of recrimination and anger flying on social media regarding AIPAC, Donald Trump, Israel’s supporters and her detractors as well.

Today is a fast day, Ta’anit Esther, commemorating Queen Esther’s request of the Persian Jewish community to join in solidarity with her as she faced the challenge of her lifetime. I dedicate my fast to similar solidarity of the Jewish community. Too much is at stake for us to stand apart in judgment of each other.

Rabbi Paula Mack Drill

A tent to call home

I have come to a “new” understanding of why the Torah spends so much time describing in such detail each of the pieces and furnishings that ultimately are put together to form the mishkan, the portable sanctuary which the Israelites carried with them through the wilderness. This tabernacle was not a typical construction project. It could not be built from the ground up, foundation poured, walls erected, plumbing, wiring and air ducts all in their proper place. No, the tabernacle had to be created section by section, each seemingly independent of the other, only to finally be put together by Moses. A tribute to the masterful nature of the design, every piece fit together as it was intended. The tent team, the altar team, the curtain team, the menorah team–each team worked simultaneously to create its assigned part in its own individual silo. Ultimately, and perhaps miraculously, everything fit together to form a suitable dwelling place for God’s presence. The success of the project points to the ingenuity of its management and to the Divine inspiration of the plan. The achievement is all the more remarkable when we consider how difficult it can be to recognize how actions inside our individual silos can affect or impinge upon the work of others and their interests.

Our neighborhood high school endured a few difficult days last week, as the students prepared for the opening of their production of “The Producers.” The school got some undesired attention over some props that were photographed hanging in the school auditorium. Swastikas, to be exact. These swastikas are part of the set of this particular play. I saw them on stage in the Broadway production. Certainly, as a Jew and as a grandson of Holocaust survivors, I found the symbols offensive, both on Broadway and on the TZHS stage. Then again, there is much that takes place on Broadway that can be considered offensive in the spirit of entertainment. Artistic productions are often meant to shock us and to shake us. I have no doubt that Mel Brooks knew his “Springtime for Hitler” would raise more than a few eyebrows along with uncomfortable laughter. The same symbols left on display in a school auditorium, however, can be quite jarring. When the unsuspecting student or parent walks into a space with these symbols present or sees them displayed on social media, it is perfectly understandable to react with hurt and fear. That is the natural reaction which the symbol evokes for many of us.

The lesson the Torah teaches me, however, is that there was a lost opportunity here, as is all too often the case. In a school that makes an effort to teach it’s children about the Holocaust, even having survivors come address the teens, this production should have been seen as an opportunity to integrate history, civics, entertainment, culture, and community building. Discussions about free speech and artistic expression–and the ways in which these things can touch certain nerves and test the limits of propriety– could have been part of the planning in bringing this production to life. Greater understanding and appreciation might have been the byproduct of such discussions. Thoughtful compromise between the risqué Broadway production and a toned-down high school version of the production might have been reached, weeks if not months before the production was set to go. In the end, the banners did not hang, though individuals wore the emblem on armbands as part of their costumes. The same conclusion might have been reached without insults and accusations had the original plan been blessed with a little more wisdom.

An event such as this–and the appalling events and attitudes we witness from some of our candidates running for office–points to the need for the exercise of a social correctness that is characterized by our proactive pursuit of teaching moments, and that isn’t dismissed with a pejorative. Insensitivity to the feelings, vulnerabilities and needs of others cannot be tolerated in public discourse, unless our intention is to create a tent that will only hold the few. Similarly, we need to practice sensitivity in the interpersonal realm until it becomes second nature.

It is possible to express one’s opinions, qualifying that they are based on a certain set of beliefs and granting that there are counterbalancing and competing claims. If we wield our opinions as weapons to shut down opposition or to denigrate those who are not swayed, any conversation is over before it starts and any possibility of learning or growth is lost. In fact, our actions and our words will be far more effective and persuasive if we consider from the outset how they will impinge on others and how they will be heard best. With a little more consideration, empathy and forethought, we may change a few minds yet, and even coax a few laughs along the way. Maybe then the sanctuary we put together will be a tent which God would be happy to call home.

Rabbi Craig Scheff

Reflecting on a Month of Awareness and Inclusion

As February draws to a close, it is time to look back to consider the Orangetown Jewish Center’s commemoration of Jewish Disabilities Awareness and Inclusion Month #JDAIM.

By the end of the month, we will have posted seven spotlights of congregants who have eloquently reflected on lives impacted by disabilities. Rabbi Scheff and I have blogged, taught and reflected in our classes on Jewish values with respect to people who have disabilities. Tonight, congregants will join with our Education Director, Sandy Borowsky, to view and discuss the important film “How Hard Can This Be.”

This coming Shabbat, February 26 and 27 will be dedicated to Disability Awareness as fellow congregant Scott Salmon speaks on Friday evening at 7:00 services. His topic is “Ask Me: the Challenges of Inclusion.” On Shabbat morning, Rabbi Scheff’s sermon will be dedicated to the topic of awareness and inclusion. After kiddush, I will be facilitating a text study tracing Jewish attitudes toward people who are Deaf or hearing impaired from the Torah through Rabbinic texts, leading up to the 2011 watershed Responsa of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards which grants full obligation and rights to Deaf people and which affirms that ASL is a language by which people can fulfill mitzvot.

At the OJC, we have much of which we can be proud. The month of February and #JDAIM, however, will only prove its lasting value if we reflect carefully on what we have learned and continue to strive toward being an ever more inclusive community.

I offer here the lessons that I have learned and look forward to your adding more to my list:

1. “Persons with a Disability” is not a useful catch-all phrase. People are first and foremost people. To paraphrase a powerful idea of the autism advocacy movement, if you know one person who has a disability . . . you know one person who has a disability. We cannot unilaterally provide services “to the disabled” as there is simply no such thing.

2. Along the spectrum of people and their families whose lives are affected by disability, there are those at one end who never identify themselves or their loved ones according to disability. They go about their lives without regard to hearing loss or the inability to walk. At the other end of the spectrum are those whose identity or whose family is subsumed by the insurmountable challenges of disability. I often think of one congregant who said to me, “We can never see a flier of an OJC activity and make plans to go and enjoy. We always must ask ourselves first, ‘What about our child? Will she be able to handle the program? And our answer is usually no. So then we ask ourselves which one of the parents will stay home.'”

3. We owe gratitude to the congregants who opened up their lives to us through their beautiful words in our spotlights. Sharing vulnerability requires courage and strength. (If you would like to write next year, let Rabbi Scheff or me know. If you do not receive emails from the OJC, you can find all of the spotlights on our Facebook page, Orangetown Jewish Center.)

4. Creating circles of inclusion is hard work. It requires the very best of ourselves. It requires us to take risks and step out of our own circles of comfort. But one thing is certain after a month of awareness: We have created a community of safety and thoughtfulness where anything is possible!

Here’s to making February all year long! B’yedidut,

Rabbi Paula Mack Drill

Circles of inclusion

“Circle time” in my 6th grade classroom is an invaluable teaching tool, especially at the end of the day, after the kids have had 7 hours of public school and another hour of religious school. I ask the students to move the tables against the walls and to pull out their chairs into the center. The students know that something different—maybe even special—is about to happen. A conversation is going to take place. Everyone will be expected to participate. There will be no corners in which to get lost.

When a couple planning a marriage comes to seek my guidance, I ask them if they have ever considered a chuppah in the round. It is certainly non-traditional; the space may not accommodate it; the aisle may not be long enough. But who wants to be in the back row when the friend you love is getting married? And who wants to be the last person standing in a row of bridesmaids, unable to witness the events under the marriage canopy?

Last week, one of my religious school students decided he wasn’t comfortable learning the dance I was teaching in our recess-time elective. Even as I explained that all the best athletes dance for balance, strength and flexibility, I realized that I could not move this boy past the discomfort of joining hands in a circle.

The intimacy of the circle can be discomforting, intimidating, even threatening. In a circle we become vulnerable; we are forced into an encounter, to see and be seen. Frontal presentation is so much safer! I can hide or find solitary space. I can sit up front and see nobody and be distracted by nobody, or sit in the back of the class and be safe from the action.

When we settle for frontal presentation, the best we can be is accommodating. But do we want to settle on being accommodating? Is it enough to make room or create space for someone, even if that space is usually on the corner or at the outskirts where it is convenient, or in the back, at the front or on the side? Most of us find security and comfort in the cushy rows of seats in our sanctuary. If we choose to sit among others, we are surrounded by familiar faces and voices. But those in wheelchairs or with walkers, the elderly and those with other disabilities have to settle for the seats on the fringes and off to the sides. It is difficult for many to slide into the pews and surround themselves by others.

We can learn an important lesson from our mishkan, our portable wilderness sanctuary, which occupied the center of the Israelite camp. The tribes encircled the holy space, directing their energy to the holy center. Situated side by side, no tribe was further away than any other from the sacred space.

Please don’t get me wrong; I love our sanctuary and generally feel that it is a welcoming space. But I have realized during this month of “awareness and inclusion” that we have work to do in consciously creating circles of inclusion. It isn’t indifference that brings us to allow others to settle on the fringes of our space. Part of it is the way we have traditionally created space for prayer, part of it is practicality, and part of it is a lack of awareness. But part of it is also our fear of circles: the fear of facing our own insecurities, our own shortcomings, our own inability to face the other.

Can we welcome one another to the circle? Are we prepared to step in, to hold a hand and to be held, to look upon another and be seen? If we are to achieve true inclusivity in our community and in our personal spaces, we need to create more circles—and open them wide.

If you haven’t been following our “Jewish Disabilities Awareness and Inclusion Month” stories, please check out our Facebook page at http://www.facebook.com/OrangetownJewishCenter. You will find a series of inspiring “spotlights” featuring members of our community whose stories will touch you and make you think about the things we tend to take for granted. We thank them for their willingness to be part of our circle!

Rabbi Craig Scheff

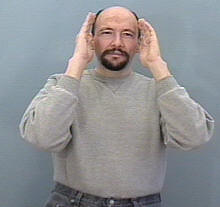

Jewish Disability Awareness and Inclusion Month SH’MA

When we teach the Sh’ma to children at the OJC, we often use sign language to provide an important pathway into the meaning of “Hear O Israel, Adonai is our God, Adonai is One.” The sign for “hear” is not used; rather, we teach “pay attention.” Hands on either side of our face draw out, focusing our attention on what is important.

As we enter the month of February, we will honor Jewish Disability Awareness and Inclusion Month with postings and congregant highlights to remind all of us to pay attention. If God is truly One, then we are all connected. A holy community like ours is not complete if we do not ensure the inclusion of all of God’s children, all created in God’s own image.

We invite you to join with us as we pay attention. May the month of February remind us to be aware and inclusive throughout the entire year!

Rabbi Drill and Rabbi Scheff

Tuesday morning quarterback

In the aftermath of the defeat, it is easy to poke holes in the game plan, to second guess decisions, to know better what would have delivered a victory. Kick the field goal with 6 minutes to go, take the points and let the defense give you another shot to win. Go no-huddle to get the “D” on its heels and slow down the pass rush. Throw to your biggest target on the 2-point conversion and let him make the play. On Monday morning, we all know the right call. Woulda, shoulda, coulda.

The Tuesday morning quarterback, however, offers an entirely different perspective. We recognize–a day removed from the emotion, the pain, the lingering heat of the moment–that more goes into a decision than the information we have. We are not the ones on the field, in the battle, feeling the ebb and flow, sensing the momentum and energy level of those truly engaged. Our new perspective allows us to forgive, to look ahead, and maybe even to acknowledge that the events over which we excoriate have no lasting affect on our happiness, our sense of self, our lives.

Perhaps it is in anticipation of our “Tuesday morning quarterback” nature that God tells us upon our arrival at Sinai to sanctify ourselves for 2 days and to be prepared “on the third day” for the revelation of God’s presence. On Day One we arrive at the mountain and encamp, probably exhausted from a two-month journey. No doubt we are dissatisfied with the accommodations, the weather, the menu. By Day Two, we all know a better place we could have stayed; some of us claim we would have been better off had we stayed in the comfortable surroundings of our subjugation. Enter Day Three, and we are looking ahead, ready to take in the sights and sounds that signal a new beginning.

The same can be said about the way we manage conflict or offer criticism in general. In the heat of the moment, our emotions get in the way of objective evaluation and constructive feedback. In the aftermath, we are good at recognizing what we would have done differently. In the after-aftermath, we can exercise empathy, understand motivating factors, evaluate our own desire to critique, and determine how–and even if–caring criticism is to be offered.

Sure, we will probably fall back on old patterns at some point. Every Sunday afternoon quarterback has a Monday morning waiting on the other side of the dawn. Win or lose, the quarterback will be second-guessed. But Tuesday will come, and with it the wondrous possibilities of the many Sundays to follow.

Rabbi Craig Scheff

Deep Listening

Join me now to consider four possible levels of conversation: Conform, Confront, Connect, and Co-Create as taught by Dr. Otto Scharmer, Senior Lecturer at MIT and co-founder of the Presencing Institute. https://www.presencing.com/

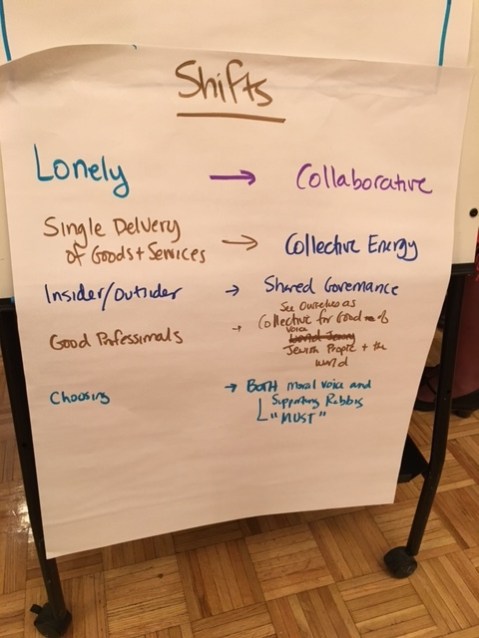

This past week, I spent two days continuing my work of visioning a new identity for the Rabbinical Assembly, the professional organization of Conservative Rabbis worldwide. We were challenged by Liz Alperin Solms and Marie McCormick, our change project facilitators, www.insytepartners.com, to understand and experience deep levels of productive conversation.

Our work over the past year has been anchored in a passion to re-envision a new path for the RA, ensuring a vital and vibrant future for Conservative Judaism.

Over the past year, I have been part of this exciting Vision Team of fifty rabbis representing a variety of years of experience and professional paths.

Throughout the work, I have been sensitive to the fact that the change work we are doing for the RA is translatable to our OJC community. I share with you now the ideas of deep conversations so that we can apply them to our synagogue life.

At the first level of conversation, Conforming, we talk “nice,” speaking to try and provide what the other person wants to hear. We use polite routines and empty phrases to conform to expectation. “Yes, of course, what you care about is important to me.” “No, of course, I don’t think that you are being difficult – I am glad to hear your thoughts.” “Sure, that’s just fine with me.”

Next, Confronting. We talk tough. We speak from an unshakable position of our own beliefs and understandings. Because we are our point of view, we become defensive. In these conversations, I am right and therefore you are not.

At the third level, Connecting, our conversations are reflective inquiries. Now I speak from a place where I see myself as part of the whole. I might still think differently from you, but now I want to know why. Rather than defend my position, I want to connect with you and come to understand your viewpoint. “I may not agree but I hope that you will tell me more about that.” “I have never thought about the issue in that way before.”

Finally, Co-Create is the fourth level. At this deep level of experience, conversation is a generative flow. I understand my place as being part of a collective, I practice stillness and experience the flow. This final level of conversation leads to collective creativity. In co-creating conversations, we might feel that something extraordinary has entered the space.

When I learned about collective creativity, I suddenly saw that our Rabbis of Tradition understood generative flow. Talmud teaches that when two people sit together to study Torah, the Shekhina, the nurturing aspect of God, rests upon their shoulders. The students of Torah lose their sense of separateness in the connection through Torah.

Our project facilitators explained that most conversations in our lives happen at one of the first two levels, and indeed, both are necessary to live successfully in the world. Sometimes we have to just be polite. Sometimes we just have to say what we really think and stand by it.

But if we want something to change and grow, we must dig deeper in our conversations. If we want our synagogue to prosper and thrive in adaptive and exciting ways, we must practice conversations at the third or even fourth level.

Scharmer’s theory about conversations for change feels very Jewish to me. To succeed as a community, we must let go of the inclination to begin every conversation from our own point of view. For success, we must say: I am part of something bigger than myself: this synagogue, this history, this particular people, this covenant with God. To fully participate in such a collective endeavor, I must listen carefully for clues about what you think and remain open to the possibility that my thinking is not enough. Together, we are stronger, wiser and more creative.

I look forward to continuing the conversation,

Rabbi Paula Mack Drill

Israel through our children’s eyes

This past Friday morning we returned from OJC’s 2015 Israel Experience, having had a wonderful time soaking up the beauty and vibrancy of the land of Israel. We enjoyed sharing our experiences with you daily on Facebook. The true authors of this guest blog entry, however, are thec hildren on our trip. These nine children, ages 6 to 21, inspired us throughout each moment of this trip.

Now, in their own words:

Rayna: Having an experience of visiting Israel is not something that everyone is able to do so, I would like to first say how fortunate I am to be on this amazing trip. An exciting ten hour plane ride across the world to the Asian continent was a pretty interesting experience on its own. This ride was especially exciting because I got to sit next to my OJC friends Victoria and Jeremy! After getting almost no sleep at all on the flight we landed and quickly headed straight to our first activities: sheep herding (not as easy as it sounds) and tree planting.

Samuel: When you think of Israel you think of Masada, the Dead Sea, Jerusalem etc. But, in Israel there are lots of interesting things that will blow your mind. Israel was the home of the ancient Jewish people, so as soon as we landed on Thursday we headed over to a place near the Ben Gurion airport called Neot Kedumim, a nature reserve representing the Biblical times. There, we planted trees because 60% of Israel is desert. At the same site we became shepherds! We played a game where one team had to herd all of the sheep into a stone circle in a certain amount of time. Some of the sheep were quite rebellious! It was a lot of fun. After that, we headed to Machane Yehuda, the “shuk.” There we walked around and saw all the different kinds of stores and street stalls. Finally, we staggered back to the hotel and collapsed.

Jeremy: At the Machane Yehuda outdoor market, we sampled all different kinds of foods, drinks, and even some spices. Some examples of refreshments that we had were smoothies (etrog flavored!), coffee, halva (compressed sesame seeds with sugar), olives, and pita bread stuffed with Georgian cheese! We’re talking about the Asian country Georgia, not Georgia in the United States. Even before Machane Yehuda, we made our way over to a spot (Tayellet) where we had a post card worthy photograph view of the city of Jerusalem. We could, see everything. We also said prayers there for wine, Challah and Shecheyanu.

The next day was in the Old City of Jerusalem, where we had a wonderful day under the Temple mount in the tunnels. We learned all about the design and structure of the stones of the Kotel. We learned about how King Herod designed his own style of stone now called “Herodian Masonry.” It was really hot down in the tunnels, but it was fun and educational!

Rayna: After two exhausting and full days, I don’t know what the rabbis and our tour guide Julie were trying to do to us children, but starting at sundown on Friday we had to walk everywhere because it was Shabbat! I actually enjoyed Shabbat because, like I told my father, it felt like a holiday that happens every weekend! On Friday night we prayed together at the Western Wall – it was really nice. We went to synagogue on Shabbat morning and even though they spoke Hebrew it was a great thing observe!

Jeremy: Saturday was very different from Shabbat at home. Here in Israel, I got the experience of walking to a synagogue with the group, including the rabbis. The synagogue was Orthodox style, with the men and women separated by a curtain down the middle of the sanctuary. They did open up the curtain for the Divrei Torah though. They were in Hebrew and I therefore did not understand what they were about. I found Shabbat to be a nice experience. For one thing, it was a day in Israel that wasn’t jam-packed with tourist activities and sights. I would totally do it again if the opportunity permitted itself.

Grace: My favorite part of the trip thus far was today and our trip to Masada. After about fifty minutes of hotheadedly hiking up the Snake Path and yelling at the more fortunate cable car riders, we arrived at the top. The magnificent view took our breath away once more. As Jeremy mentioned, King Herod built part of the Kotel, but he also created the palace on Masada. After his death, it was used for a Roman army base. When the Sicarii, or Dagger Men, of the Jewish rebels infiltrated the base, they used the palace as a safe hiding space for three years, until the Roman soldiers finally made it to the top. The Romans surrounded the Sicarii. In the depths of their desperation, they decided that they would rather kill themselves than surrender to the Romans and be killed, mutilated, or sold as slaves. It is told that no one survived. We learned that what actually happened up on Masada many years ago is a little unclear. All I know is that the view there is beautiful and I liked hearing the various stories, however horrific they may have been.

Our next stop was the Dead Sea. This sea is so salty that it is impossible to have any life there. This is why they call it the Dead Sea. The salt also causes anything to be extremely buoyant, so you can literally float on the water. It’s a phenomenon that is so difficult to explain, but so amazing to experience. When we arrived at the shore we saw people walking around with the infamous mud spread over their bodies. The salt in the water magically made it completely buoyant! It was amazing. At first, I was nervous about experiencing something so odd to me. I didn’t understand how salt could make water turn into something so easy to float in. Once we finally were able to lay back in the water and experience the impossible, there would be no turning back from the fun. We laughed with our friends, attempted to get into the weirdest positions while still floating, and just relaxed in the cool sea.

My experience in Israel so far has been an amazing experience, a phenomenal one. I have loved it with every bit of my heart, and I hope, sincerely, that I will come back soon.

Milo: This winter break, I was lucky enough to get to travel to Israel. Today we packed up our suitcases to head up north. On the way out of Jerusalem we stopped a few times. Our first stop was Yad Vashem. While we didn’t go inside the museum itself, we saw some of the monuments outside of it. The first thing we saw were the trees planted in honor of the non-Jews (righteous gentiles) who worked hard trying to save Jews. There were trees lining the stone path for a few hundred feet, and each tree had a plaque with the name of the honored person. The path that the trees bordered led toward two statues. The first statue was an engraving of a group of Jews being taken to a death camp. They looked frightened and broken. Their heads were bent, and in the background you could see Nazi soldiers’ with bayonets and helmets herding the Jews forward. The second statue was an engraving of Jews who looked strong and prepared to fight.

These words and images are just a sample of what we were blessed to hear and see throughout our time in Israel. Most meaningful of all was the desire expressed by each child on the trip: to return again soon; to continue exploring Israel, her history, and her connections to our Jewish identities; to be a part of supporting Israel as she strides into the future with hope.

With great appreciation for these days with our OJC Family,

Rabbi Ami Hersh and Rabbi Craig Scheff

Joseph and Anakin, children of grace

Long ago, in a galaxy far away…. The glue has once again been provided to connect the generations with one another. The themes are as eternal as they were before; the myths are as powerful as ever. The child within the oldest of us is awakened, and the wisdom of the ages enters the heart of our youngest.

These moving narratives are treasured by us, in part, because they imaginatively capture the metaphors that give expression to our truths. The battle between forces of light and dark, the struggle between our innate inclinations (the yetzer ha-tov and the yetzer ha-ra), the propensities we carry towards hope and despair—these most basic conflicts play out in the scroll and on the screen before our eyes in living color.

I admit that I am slow to admit that anything is coincidence. It is a gift that the newest installation of the Star Wars saga hits the silver screen as we are immersed in studying the portions of the Torah retelling the story of Joseph and his family. I can’t help but see the parallels between the narratives of Anakin Skywalker and Joseph.

Both boys discover at a young age that they have abilities that distinguish them from others. Both sense that they are destined for something greater than their stations in life. Both are sold into servitude. Both will ultimately rise up to be second in command of their respective empires. Both live with the loss of a mother and with separation from family.

Their paths, however, diverge due to the ways in which they confront their respective circumstances. Driven by the anger generated by his sense of loss and by the fear of losing those he holds dear, Anakin is drawn to the Dark Side. Joseph, on the other hand, recognizes that his gifts are but an instrument of God, to be used for the furthering of the Divine Will (also known as the Force?). He is moved beyond his selfishness and ego by his faith in the goodness of God and his trust in the desire of others to redeem themselves through righteousness.

Ultimately, Anakin redeems himself. It is a sign for all future generations that they, too, can overcome the Dark Side to choose a path of grace. Is it coincidence that the name “Anakin” can be translated to “child of grace”? (Okay, I made that up, using the Hebrew root for “Ana,” or Hannah, meaning “grace,” and the Germanic origin of “kin,” meaning “give birth to.” Thus, child of grace!) Joseph redeems himself as well, and teaches his brothers and all future generations that they can redeem themselves through acts of faith. The seemingly endless battle between good and evil is perpetuated by those who give in to anger, fear and loss. While I won’t see the new movie until next week, I am fairly certain that the narrative will remind us, during these troubling times, that our actions cannot be dictated by fear, and that our actions of faith and trust may sometimes give way to betrayal, but ultimately are the only way to forge a path towards redemption.

May the Force be with us,

Rabbi Craig Scheff

Recent Comments