Making a Minyan because of Kindness

My teacher, former Chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary, Dr. Ismar Schorsch, likes to say that the requirement of a minyan is the secret of Jewish survival throughout the centuries of dispersion.

Every week in News You Need to Know, we remind you to fulfill your obligation to attend a morning or evening minyan.

Every OJC member is assigned a number which represents the day of the month that one is required to attend the minyan at the synagogue.

With regard to a prayer quorum, we singularly use the language of obligation and responsibility. On the one hand, these words are appropriate. Gathering ten to say prayers that praise God’s name publicly is a mitzvah, a commandment of Judaism. On the other hand, perhaps we should instead employ the language of loving kindness. Gathering for a minyan provides a setting for chesed (loving kindness). How so? One of the most painful elements of modern life is a sense of isolation and loneliness which it can foster. A minyan just might be an antidote. I formulated this idea over the past week as I davened with different kinds of OJC minyanim.

Last Tuesday morning, ten of us gathered at Esplanade on the Palisades to make a minyan for Estelle Sollish, our much loved congregant who recently moved there. Bringing the minyan to her was a sign of devotion and our desire to ease her transition to a new living situation.

On Thursday morning as we stood at the Torah, one of the people of the minyan added the name of a loved one during the prayer for healing. The tears in his eyes bespoke a concern and worry that he was not yet able to articulate. But the minyan allowed him a safe space to be vulnerable.

On Saturday afternoon I chanted the words of the memorial prayer on behalf of a congregant’s mother whose twentieth yahrzeit falls this week. As I prayed that her mother’s neshama would have an aliyah, I saw that the gathering of fellow congregants gave her permission to express her grief even after all these years.

Last night there was a minyan at a shivah house. As the family gathered close for comfort, the arrival of fellow congregants brought the sure sense that they were not alone.

Admitting what we need, asking for help, showing our vulnerability — can lead us out of isolation and into community. A twenty-minute prayer service can accomplish all that. Mark Nepo has written: “As water fills a hole and as light fills the dark, kindness wraps around what is soft, if what is soft can be seen.” It is indeed the obligation of a community to create minyanim so that people can pray together. I have no doubt that Dr. Schorsh is correct in his estimation that the minyan has kept the Jewish people together. But perhaps the most important reason for a minyan is that gathering together allows others to be vulnerable, to know one another, to seek a path away from loneliness. Gathering to be one of ten allows us to be our very best selves through this act of loving kindness.

#whoweare

This past week, the Jewish Federation and Foundation of Rockland issued a statement, which we shared to our synagogue community, in response to the recent publication of the Movement for Black Lives’ platform. I had a feeling that the statement would elicit a range of responses, and my sense was rewarded with three messages, each very different in its perspective. With each passing day this week, following social media and the many (mostly Jewish) media outlets, I gained several more perspectives in response to the platform. I have tried to find my personal response inside these many perspectives, but none entirely gives voice to exactly how I feel. So perhaps, if I can lay out my responses for you, you can come to a conclusion of your own. I can, however, offer you from the outset one ultimate conclusion I have reached: if you truly care about where to stand on this issue, you must dive in deeply. Wading through the waters from the surface will only serve to reinforce preconceived notions and biases, in which case you might as well not even bother taking the swim.

To summarize the issue in its most basic terms, the published platform of the Movement for Black Lives (note: they are a subset of organizations affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement, but they are NOT synonymous!), in an extensive and far-reaching statement of “policy demands for Black power, freedom and justice,” includes a section on investment and divestment: “We demand investments in the education, health and safety of Black people, instead of investments in the criminalizing, caging, and harming of Black people. We want investments in Black communities, determined by Black communities, and divestment from exploitative forces including prisons, fossil fuels, police, surveillance and exploitative corporations.” Among the many detailed demands put forth in this section, in calling for a decrease in military spending and aid, the platform singles out America’s complicity with Israel “in the genocide taking place against the Palestinian people.” The platform further states that “Israel is an apartheid state with over 50 laws on the books that sanction discrimination against the Palestinian people.”

So here is where the conversation gets tricky, especially in a community where so many people have pledged support for the Black Lives Matter effort but who also care about protecting Israel’s interests against deligitimization and the growing BDS (Boycott, Sanction and Divest) movement.

My observations:

- Everyone should read the entire Movement for Black Lives platform. It is important on so many levels, and there is so much to learn about the institutional challenges we as a society face in battling economic inequalities, social injustices, and racial biases in America. (Click here, please, to access the platform.)

- “Genocide” is a loaded term, especially for Jews. While others may look to expand the definition of the term for their own purposes, or are not sensitive to the impact of that word on others, some Jewish people go to the other extreme, claiming ownership of the word for their personal, unique and incomparable historic experience. Most Jews are extremely sensitive to the use of that word being directed at Jews or the Jewish state. In the words of my colleague Rabbi Shai Held, “The Occupation has caused immense suffering to Palestinians, and in my estimation, it has caused profound moral and religious rot in Israel. And the silencing and condemnation of so many serious, passionate Jews who have been critical of the Occupation has done profound damage to the American Jewish community (and to Israel too). But an occupation is decidedly not a genocide. And to suggest otherwise is to demonize and vilify the Jewish State based on what amounts to a libel.”

- Naming Israel an apartheid state is absurd, and exposes ignorance at best and bias at worst. Recent United Nations reports of Hamas using humanitarian aid for the purpose of building tunnels into Israel from Gaza should serve as a good reminder for why security fences and checkpoints exist in certain population areas. Moreover, the economic and political freedoms and legitimate opportunities that Arab Israelis, Muslims and Christians, Blacks and other minorities enjoy in Israel should render any accusations of apartheid as malicious and illegitimate. This is not intended to ignore the challenges faced in Israeli society, where prejudices and institutional inequalities also exist. But by any objective standards, these challenges do not render Israel an apartheid state.

- Any intersection of the Black Lives Matter with the BDS movement sells short and undercuts the legitimacy of the BLM movement. Most in the mainstream agree that BDS is veiled anti-Semitism, that it does not advance the chances of peace between Israelis and Palestinians, and that it does not acknowledge the realities of the region.

- Jews have historically walked proudly with other civil rights’ movements, especially in 1960s America, because of our own historical experience and the Torah’s socially progressive ethics. But the Movement for Black Lives is not the civil rights movement of the 1960s. It sees itself, in its own language, far more aligned with the more radical Black Power movement, engaged in a struggle against White supremacy and imperialism around the globe. To what degree, then, is this movement interested in partnerships with those who have been associated with privilege and imperialism? That question is yet to be answered.

- “All lives matter” is not an appropriate response to the “Black lives matter” assertion. Just as we, as Jews, see our historical experiences and suffering as unique, so too blacks have a unique history, experience and place in society today. We who are white Jews may be able to sympathize, but we cannot empathize with those who are black. I have learned this from the stories of black Jews in our community; I have learned this from white Jewish parents raising black Jewish children. They face a unique set of challenges in this society, Jewish or not. Yes, all lives matter. That is one of our central values as Jews. Even so, the obligation to the stranger in our midst is a separate Jewish value, equally as important. The plight of black people in our society warrants separate consideration.

My conclusion:

“We” are not mutually exclusive. “We” as a Jewish community are constituted by individuals of many colors, black, white, and others; we are Jewish and non-Jewish; we are liberal and conservative. As such, we need to recognize that when issues such as this one arise, some of us may be affected differently than others. Our internal response is as important as how we respond to the outside world. Unified or not, that response needs to reflect an understanding of, and be sensitive to, the diversity that “we” represent. Hopefully, our response can always reflect the unity of our shared values. If the 9th of Av, whose fast is observed Saturday night into Sunday, is to teach us anything, it should at least teach us that is who we are.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Craig Scheff

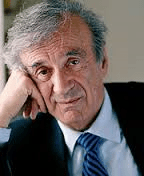

Elie Wiesel, True North

Like so many, I felt great sorrow upon hearing of the death of Elie Wiesel on July 2. I felt bereft at the loss of such an iconic man, one who served as a moral compass for the world almost against his own desire. In the two weeks that followed his death, I have read many meaningful eulogies and tributes and decided that I had no insights of my own to offer. I never met Mr. Wiesel. I did not study with him or serve on a board with him. I only heard him speak publicly once though I read every book Wiesel authored. His wisdom holds an indelible place in my Jewish identity. How many of us could claim the same? What did I have to add to the conversation?

In the two weeks since Wiesel’s death, the world has continued to implode in a myriad of frightening and devastating ways. It feels like we have entered a dangerous, stormy night in a rudderless ship. . . and we have lost our compass. For many of us, Elie Wiesel represented our True North. Bracing myself with each new piece of information about bombings, murders, demonstrations, ugly campaigning and economic threats to stability, I realized that I do have something to say.

I was only 12 years old when my older cousin Beth gave me Night to read on the flight from Florida back to Maine.

When I got off the plane, I collapsed into my parents’ arms sobbing. They thought that I had missed them during my week-long vacation, but I soon explained that the tears were a response to the book I had just completed. I had come to understand in my very soul the horrors of the Holocaust and its implications for me as a Jew. Reading Night was most definitely my awakening to the reality of a world with evil in it and to the precariousness of life as a Jew.

Twenty-four years later, as I sat in a hospital room witnessing my mother’s dying, it was Wiesel’s memoir, All Rivers Run to the Sea that I read. That haunting book of hope and disaster is forever entwined in those lonely frightening days. Wiesel’s book and my mother’s death taught me that life followed by death is a reality we cannot deny.

Wiesel’s lessons thus form bookends for my first awareness of loss when I was a child and my acceptance of loss as an adult. Acceptance does not mean indifference. Acceptance dictates that life must be fully embraced in every moment. Wiesel said, “I had all the reason in the world to be angry at the world, at God and at the Other,” but he refused anger as his response to his life story. He chose education, advocacy and memory.

I am struck by the fact that Orangetown Jewish Center began a campaign to fund a memorial to the Shoah at the entrance of our building in the same week that we lost Wiesel. How beautiful that we are creating a place to congregate, contemplate and educate. Each of us will be able to embrace and draw strength from the fact that none of us stands alone. At the OJC, we are all part of a caring community committed to ending intolerance and injustice. We are committed to remembering for the sake of creating a safer, better world. I know that we will carry on the legacy of this great moral leader.

As long as Elie Wiesel lived in this world, we could count on his opinions, his humble yet powerful statements, his decisive writing, his willingness to scold world leaders if necessary. The world feels like we have entered a dark and stormy night indeed without a True North. But together, we will find our way out of the darkness, out of the Night. By remembering and acting on memory, we will ensure a better world for our children and grandchildren, nieces and nephews, for all the children of tomorrow.

Join me as I dedicate myself to acting in his memory. No one person can replace such a moral giant. But each one of us can do our best to stand up for the values that he held most dear. In this way, we will continue Wiesel’s legacy of repairing the world.

Never forget. Always remember.

Rabbi Paula Mack Drill

Speaking as prophets

Today, Israel and those who love her mourn the brutal murder of 13 year-old Hallel Yaffa Ariel. The leadership once again searches for balance as it reels from the blow, struggling to arrive at the “appropriate” response. I would not dare offer an opinion on the matter, even if I could formulate one. As I prepare to share this message, another terrorist attack is unfolding in Bangladesh, with several already dead, dozens held hostage and ISIS claiming responsibility. I pray that the perpetrators be brought to justice and that the hostages emerge unscathed. But even as we struggle with how to respond to our neighbors and to the world in light of these events, I am still compelled to speak within our family to an issue that must remain at the top of our agenda as Jews. t is an issue of self-care. And such is the nature of these times. If we cannot care for our own well-being, we won’t be any good to anybody else. To that end:

Some of my colleagues believe that in this day and age rabbis must function as prophets, taking public stands on political and social issues from gun control to refugees to presidential campaigns. Judaism, no doubt, has what to say about all these topics of the day and more. As a rabbi, however, I see it as my task to educate about what Judaism says to all sides of these issues. After all, we know that Judaism rarely offers a single answer to any question, sometimes only offering another question in response. Being a rabbi certainly doesn’t qualify me as the authority on all topics that affect our society; being a Jew certainly doesn’t qualify me as owner of the only truth.

Jews of Israel and Jews of the Diaspora must take back from the hands of the self-proclaimed prophets ownership of God’s word. Each of us is a prophet, each of us hears God’s word. When we own this fact and tear down the false altars that have been erected by those who have hijacked our tradition, Torah will once again emanate from Zion, the word of God from Jerusalem. Her ways will be pleasant, and her pathways will be peace. Then we will certainly have what to tell the world.

49 Days of the Omer; 49 Innocent Victims

When this past Saturday turned into Sunday, it was the first day of the holiday of Shavuot. We had finished counting 49 days since Passover. It was time to receive Torah. Together with about eighty congregants, I was cozy in the synagogue, studying words of Torah in groups of four, eating coffee ice cream with chocolate sprinkles.

When the sun rose on a new day, I was sleeping for a few hours before holiday services began again at 9:00 a.m. I was a bit groggy as I began chanting the blessings of the morning, but I felt happy and fulfilled in one of my favorite holidays, when we would be celebrating the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai. I was blissfully unaware of the outside world.

When this past Saturday turned into Sunday in Orlando, Florida, a mad man whose soul was poisoned with hatred and a fanatical view of life was holding more than 100 people hostage in a nightclub intended as a gathering place for celebration. While I was studying words of Torah, he was shooting 49 people dead and wounding 53 others. In the morning, the world that was attached to media started reeling from the news of yet another mass murder, another act of terrorism, a horrifying targeting of the LGBTQ community, an attempt to bring down the joy of Pride Month.

As Saturday turned to Sunday, I was discussing the meaning of: “You shall be holy because I the Lord your God am holy.” In my havruta (study group), we thought that if we could possibly agree on a definition of holiness, we would know exactly what God expects of humanity and particularly of Jews. We would have the key to making our world a better place. At 1:30 in the morning on Sunday, it all felt so simple and uplifting. And all the while, a terrorist was shooting people dead.

How can there possibly be any sense in the world? How can God possibly expect us to be holy?

Since Sunday, people I have spoken with want to know how goodness can possibly matter in the face of evil. My stubborn answer is that goodness is the only thing that does matter.

Every act of kindness takes away the power of hatred and cruelty. I refuse to become a nihilist or a pessimist. Being an optimist is not frivolous or naïve or weak. Being an optimist in days like these requires immense courage.

Author Rebecca Solnit says: “Hope is not a lottery ticket you can sit on the sofa and clutch, feeling lucky. It is an axe you break down doors with in an emergency. Hope should shove you out the door, because it is going to take everything you have to steer the world away from endless war, from the annihilation of the earth’s treasures and from the grinding down of the poor and marginal.”

This past Sunday, the Jewish people celebrated Shavuot, the Festival of Revelation. In our all night study at the OJC, Rabbi Scheff taught that creation and revelation lead us toward redemption. Redemption will not fall out of the heavens above. The promise of redemption is in our hands, and it is what keeps us moving forward with optimism and hope, believing against all odds that we can repair the world. Join me please. Act by act, moment by moment, we can bring redemption to a world desperately in need of repair.

Rabbi Paula Mack Drill

A prayer in the wake of disaster

Tonight, however, this open heart is a curse. Because I feel the suffering of my sisters and brothers. And I absorb the taunts of those who wish my children harm. And I shudder at the sounds of laughter and rejoicing over spilled blood. And I don’t see in the face of my neighbor another who is content with being my neighbor. And the voices of reason that provided me with hope just hours ago have been drowned out by the crowd applauding the gun shots in the theater of the absurd.

So in this moment I find myself closing my open heart to protect myself from the pain of all that suffering. And as the heart closes, I feel it hardening in anger and despair.

Please, God, slow my racing heart and grant me a few hours’ rest. And in my sleep, soften my heart again. Because I need to love. And I can’t truly love–even my own children–so long as this hardened heart beats within me. And once I can feel again, let the blessing-curse of my empathy move me to heal the sick, to comfort the mourner, and to set out rebuilding a shattered world.

In the words of Jeremiah from this past week’s haftarah, “Heal me, Adonai, and I will be healed; save me and I will be saved.” Give me reason to praise You.

Wedding Day on The Border

After a wedding errand in Sederot with Sagi’s mom Racheli, we waited for a long line of trucks to go by before we could turn left onto the highway back to Mefalasim. When I asked her where all the trucks were coming from, she shrugged and said, “from Gaza”. Why? “They are returning from dropping off the day’s humanitarian aid, food and medicine.” Every day? “Sure. We bring them supplies every day.”

Stymied, I tried to wrap my mind around the simple fact of Israel’s taking care of people in Gaza, the neighbors who are still trying to build terrorism tunnels under the kibbutzim where Sagi grew up.

Racheli says that she does not think about missiles or terrorist attacks when it has been relatively quiet for a period of time. She tells me that she blocks it all from her mind. I am just a visitor, and I am the opposite in my response. When I am here in the south, all I can do is think about that long period of time when missiles fell every day on Sederot and the surrounding kibbutzim of Shaar HaNegev. Long before Iron Dome, missiles reached the ground and took away peace of mind and people’s lives. Since the miraculous protection of Iron Dome, still no one here lives with a complete sense of security.

I think about it all the time. I look at the waitress at the restaurant in Sederot and imagine her as a young girl, running for shelter with 15 seconds notice. I sit with Sarah as she has her hair done for the wedding later today and wonder how Shupan kept his business running through those years.

I sit in Racheli’s classroom at Shaar HaNegev High School as she presents an experiment to her chemistry students and notice the sign just next to the whiteboard. It is a sign we would never see in America: in case of tzeva adom, a red alert, do not leave the building. I observe Racheli’s students and acknowledge to myself that they have never lived in a world without threat from their neighbors.

At the entrance of Kibbutz Nir Am, on the way into the guest cottage, I pause to think about the very beginning of Protective Edge… and of two Israeli soldiers who were killed here. On my morning run, I cannot avoid looking at the barbed wire surrounding the entire kibbutz.

But then, I see a sign. I mean that I see a sign and also that I see a sign! It says: Beware! Narrow Bridge.

And I complete the significance for myself: all of the world is just a narrow bridge, and the most important thing is not to be afraid.

Praying every day for peace for Israel, Rabbi Paula Mack Drill

Shabbat Here and There and Now and Later

One of my favorite Talmudic teachings asks what one should do if she is lost in the desert and does not know what day it is. How can she know when it is Shabbat? The rabbis answer that she should count six days from the time she remembers and the seventh day will be Shabbat. [Talmud Bavli Shabbat 69b] I love this response because it reminds me that Shabbat is not just a day on a calendar but a sacred time we can enter once a week… and a time that enters us. When Tradition tells us that we receive neshama yeteira (an additional soul) every Shabbat, I think it is talking about this mystical, tangible quality time takes on when it becomes holy.

I was thinking about this Talmudic source as we entered into Shabbat here in Tel Aviv. When I am away from Orangetown Jewish Center for Shabbat, I picture myself sitting in the sanctuary before our stained glass windows and colorful ark curtain as the room fills up with people I love. But of course, I also enter into Shabbat where I am.

Wherever I go and whatever is happening around me, Shabbat enters me and I enter Shabbat… even in Tel Aviv, the City that Never Sleeps. (Ask any Israeli and they will tell you that New York comes in second to Tel Aviv.) On Friday afternoon, as we made our last minute purchases of challah and fruit in the shuk (market) and I dashed back to Sarah and Sagi’s apartment to check on the chicken soup,

young people in Tel Aviv were settling into pubs and cafes for the beginning of their weekend.

We ate Shabbat dinner on the roof of Sarah and Sagi’s apartment and Ben’s voice reciting motzi mixed with the sounds of a band playing at a bar just outside the Kerem haTemanim neighborhood. In the quiet peace of our Shabbat, I blessed my children and we ate our meal.

On Shabbat morning, we walked to a Masorti synagogue, Kehillat Sinai, where we were warmly greeted and where I was asked to help out as a gabbai. The chanting was different, the faces were new, but the atmosphere was friendly and open. It reminded me of the OJC in its lively community feel.

We spent Shabbat afternoon on the Tel Aviv beach, admittedly one cannot do that in Orangeburg! But while I was here in Israel for Shabbat, I was also in New York for Shabbat, and this is where the teaching from Shabbat 69b comes in handy. When I entered Shabbat, my community was in the midst of busy Friday afternoons back home. When I was hearing the Torah reading of Behar, everyone in New York was sound asleep. When I was relaxing on the beach, the congregation was hearing our intern Paula Rose give her sermon. And when Shabbat went out and I counted the twenty-ninth day of the Omer, my friends at the OJC were beginning their Shabbat naps! How could I be two places at once?

Shabbat enters me and I enter Shabbat. It’s not just time on the clock or a day on the calendar. Shabbat is far more than that. Shabbat is a place I go once a week to replenish my soul. Whether here or there, whether surrounded by people keeping Shabbat or having Saturday morning eggs at a café on Dizengoff, it’s all Shabbat. What more do I need?

See you all next Shabbat at the OJC! Blessings from Israel,

Rabbi Paula Mack Drill

Remember to rejoice

Israel gives Memorial Day it’s due.

Yom Hazikaron, Israeli society’s day to remember it’s fallen soldiers and those lives lost to terrorist attacks, weighs heavily on Israel’s communal heart. As the sun goes down on the day, however, a switch is flipped, and an unbridled joy sweeps across the country. Riding a wave of relief, young and old take to the streets to sing and dance, that same communal heart racing to celebrate Yom Ha’atzmaut, Israel’s independence day.

In Israel, our six degrees of separation are reduced to two. Everyone knows someone who has experienced the personal loss of a family member, friend or acquaintance to war or terror. So while the community shifts into celebration mode, many individuals remain clenched in the pain and sadness of the national day of mourning. And those who are dancing know that some among their friends can’t bring themselves to do so. Still, the memorial day adds meaning and purpose to the independence day that follows. It is the broken glass at the wedding. The joy of the second is an informed joy, and the loss remembered is appreciated for what it has made possible. The losses have not been in vain; the sacrifices are not unnoticed or unappreciated. Sadly, Yom Hazikaron is the silver platter upon which Yom Haatzmaut is served, and the platter needs to gleam freshly polished if the main dish is to be enjoyed.

I wonder what these two days will look like when Israel is 340 years old. Will we still be reading names of fallen soldiers and victims of terrorism before celebrating Jewish sovereignty, or will Israel have achieved six degrees of separation from the suffering? And what might that look like? Could Israel’s national days become back to back days for barbecuing and hitting the malls for sales? Somehow, I don’t think so. I imagine that even, God willing, when there are no fresh names to read, and the thousands who have died in sacrifice are generations in the past, the proximity of these two days will carry the same impact as the moment “If I forget you, Jerusalem, let my right hand wither” is recited under the chuppah.

If you’ve ever come to our synagogue, you’ve passed by the Camp Shanks memorial, a site erected in honor of those soldiers who passed through Camp Shanks on their way to Europe in World War II. I see it every day of my life (except sick days or a rainy Shabbat). It is a powerful reminder that even a country without enemies on its borders has endured loss and has demanded sacrifice, which all too often go unappreciated. I don’t know how many years 9/11 will continue to be remembered by so many of us as a day of solemn assembly. I don’t think that the degrees of separation from personal loss should diminish the respect and appreciation we show for the sacrifices that have assured our freedoms.

This year, at 9:45am on Memorial Day, immediately following an 8:45am morning service at which a memorial prayer will be recited as part of our Torah service, I will walk down the street to stand at the Walkway of American Heroes. I will be surrounded by veterans and families of veterans, by those who have known loss and those who have known service, by local community members who make remembrance a part of their joy. I hope I will be surrounded by you.

Rabbi Craig Scheff

Thoughts on Joy: Moadim l’Simcha

The first two holy days of Passover came to an end last night and with the holy days, so went my children. As we made Havdalah, Josh left for the airport to return to Israel and his IDF unit. Noah returned to Maryland, Ben to college finals, and soon Sarah and Sagi will return to Israel as well. Moadim l’simcha, we say, may these middle days of Passover be filled with joy. Forgive me if my joy feels a bit diminished.

And I really mean: Forgive me. I have so many reasons to be filled with an abundance of joy. Like Elijah’s cup at the seder, the joy should be flowing over the top of the cup.

All four of my children became “all five of my children” this year as we added Sagi, a son by marriage to our ranks. On the Sunday before Passover, our daughter Sarah and Sagi stood under the chuppah with Rabbi Craig Scheff officiating. For anyone who might have been second guessing attendance at a simcha on the last really great cleaning/preparation day before Pesach, Rabbi Scheff told us that celebrating the wedding was exactly the kind of Passover preparation we should be doing. The ruach of the wedding was an experience of simcha that no one in our families will ever forget, pouring joy into my cup.

My own preparations for Pesach were put into perspective with absolute clarity. I could not have angst and agita because there was simply no time. On Monday we were serving bagels to thirty out of town guests. On Friday, we were sitting down to our family seder. The lived-understanding that my best was good enough and that the seder is meant to be completely a time of rejoicing freed me from years of self-imposed rigor.

I have taught for years that we don’t need to be tortured in our Passover preparations. This year I walked my talk. The sense of freedom of the seder was another level of simcha poured into my cup.

It was a blessing to celebrate the first two days of Passover with such an abundance of old and new family, a blessing that I don’t take for granted.

Two wonderful seders, sunny days, lunches of matza lasagna with friends, long walks with my new machatenasta (Yiddish for mother of my son-in-law) enhanced the beauty of the chag. The sense of quiet contentment is another kind of simcha to add to my cup.

Still, as the holy day ended last night and the middle days of Pesach began, I felt the diminishment of my joy as one by one, the Drill children and members of the Fainshtain family started peeling away, leaving us with great memories and (forgive me) matzah crumbs. But here is where Jewish ritual came to the rescue, reminding me that given a choice between feelings of loss and feelings of gratitude, I can choose gratitude.

Last night we counted the second day of the Omer. As we continue on the calendar arc from Passover to Shavuot, from redemption to revelation, we count up, not down. Each day toward the holiday of Shavuot reminds us that we choose to make every day one of meaning, to make every day count. I can let go of the lessons learned about simcha or I can hold fast to joy by being grateful. Forgive me If I choose joy!

Moadim l’simcha! Rabbi Paula Mack Drill

Recent Comments