Lo Levad, You are Not Alone…easier said than done.

When I think about my dad at home through all the years of my growing up, I think of him as alone. And when I think about my mom through those same years, I think of her as lonely.

Living with bipolar disorder, my dad spent months at a time inside our house, often in his bed, almost always alone. My mom went out to work every day, and my brother and I went to school. When we got home, there he was, on the couch, watching television. I was a kid. It never occurred to me to wonder about how alone he was.

In the 1950s and 1960s, no one understood my father’s mood swings. My parents’ friends wondered and perhaps pitied, but mostly stayed away. My dad‘s parents fretted that they had done something wrong to cause such brokenness. My mother’s parents urged her to leave my dad, and bring my brother and me to live in their house. Instead, my mother stood by my father, the love of her life. She held him and us together. There were no support groups for her; synagogue was not a safe place; and her friends were not equipped to understand. I wonder who could have possibly listened to her without judgment even if she could have articulated her sorrow and her rage. She must have been very lonely.

I thought a great deal about my parents yesterday as we celebrated a beautiful Shabbat of mental health awareness at OJC.

Thanks to the dedication and planning of #OJCSupportsU chairs Miriam Suchoff and Mark Brownstein, congregants experienced a wealth of opportunities to open our hearts and minds, and to create feelings of well-being and happiness – keystones to nurturing and sustaining good mental health. Through meditative prayer, singing, text study, and guided building of relationships, we practiced experiences that promote resilience.

We walked in silent meditation from the Daily Chapel to the bima in the Sanctuary to receive Torah, a powerful reenactment of Mount Sinai where everyone received Torah in his or her own way. God does not see anyone as broken; everyone is created in God’s image. We walked together as a community, from the four-year-old twins skipping to the 90-year-old couple walking carefully with canes. Being together in a community where everyone is accepted as “just fine,” just the way they are, is a most powerful sustainer of mental wellness. Everyone who was in synagogue yesterday felt this crucial teaching in our very souls.

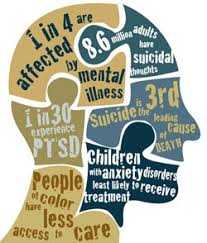

But what about everyone who was not able to be in synagogue with us? What about the people who struggle with mental illness in their homes or in facilities and cannot leave, trapped there, unable to enter into our community of faith? What about the caregivers of those people, too exhausted and fearful of stigma to come out and join us in community? They probably do not see a sanctuary, rather they see an unbearable barrier to entry. How can we begin to change this reality for Jewish people who feel isolated due to mental illness?

We must continue to speak out. We must work hard to enable people to feel safe enough to be vulnerable in our sanctuary spaces.

There are many opportunities in the month of May, #MentalHealthAwareness.

Wednesday, May 15 at 7:00 pm at the Rockland Jewish Community Campus, Rockland Jewish Family Service and Board of Rabbis present Lo Levad, You are Not Alone.

Thursdays, May 16, 23 and 30 at 7:30 pm at OJC, join Rabbi Scheff to study Jewish sources and mental health issues.

Thursday, May 30 at 6:30 pm at OJC, join me and Amichai Margolis for a spring time service of healing and harmony.

If you are struggling with mental health issues and you feel alone, reach out to your rabbis or to #OJCSupportsU in any way that you feel able so that we can meet you halfway. Even if you can only reach out a very short distance, we will meet you the rest of the way.

If you are lonely because you are a caregiver for someone you love struggling with mental health issues, we invite you in to listen, share and strengthen yourself.

You might feel alone and you might feel lonely. We want to provide a community for you in whatever way we can, not just in the month of May, but always.

Yesterday, before the Musaf Amidah, Mark Brownstein read Merle Feld’s poem, “Dreaming of Home.” To me, it reads as a clarion call to all homes of worship to be places where people are safe and known.

We want so much to be in that place

where we are respected and cherished,

protected, acknowledged, nurtured, encouraged, heard.

And seen, seen

in all our loveliness,

in all our fragile strength.

And safe, safe in all our trembling

vulnerability. Where we are known

and safe, safe and known —

is it possible?

In closing, I dedicate this post on Mother’s Day to my mother, Frances Weisberg Mack z”l, a woman of extraordinary strength and dedication.

With prayers for a refuah shlayma, a complete healing, a healing of body and healing of spirit,

Rabbi Paula Mack Drill

Finding solace after Passover

On a 30-mile sunrise trek out of and back into Mitzpe Ramon, my colleague and fellow rider Rabbi Ed Gelb introduced me to the idea of the “solace of silence.” Or was it the “solace of solitude?”

Reflecting on my recent participation in the Ramah Israel Bike and Hike in the Negev (which included 250 miles of biking over 5 days the week before Passover), I sat with my memories of the silence, the solitude and the solace I experienced in the open spaces of the desert. Given the timing of the trip, I was particularly excited to travel along the Jordanian-Israeli border and the Egyptian-Israeli border at the same time of year the Israelites of the Torah would have exited Egypt. Due to this year’s very wet winter in Israel, the Negev was green along the “river” beds that would carry the rains. I was reminded of the words of Psalm 104, which we read just this morning in celebration of the new month: “You make springs gush forth in torrents to flow between the hills.” I imagined the flock that accompanied the Israelites feeding on the greenery, the children picking the purple and yellow flowers. I wondered whether the winter that preceded the exodus was an unusually wet one in God’s anticipation of the challenging journey.

As I rode with my group (we “Bogrim” were the intermediate riders, encompassing a wide range of biking abilities), we’d often get spread out along our route. Sometimes we’d be divided into small packs, where we could push, encourage, joke with, and occasionally sing to one another. Sometimes we’d feel entirely alone on the road, though there was always someone just a minute ahead or a minute behind us.

The moments of community and the moments of solitude in the open and quiet space of the wilderness gave me a new perspective on the Israelites’ journey from slavery to freedom. I’d always understood the desert as a necessary transformational experience for our people, but never fully appreciated the effects of the surroundings on the fledgling community. Barren, silent and expansive, yet beautiful, peaceful and awe-inspiring, the Negev invited me to clear my head, to shed my burdens, to breathe deeply into my faith and to connect at a soul-level with the land, the journey and the people sharing both with me.

Wanting to pursue the topic further, I searched for the book that Rabbi Gelb had mentioned. As it turns out, I had the title entirely wrong. The book he referenced that morning was The Solace of Open Spaces by Gretel Ehrlich, a collection of essays about the author’s life and encounters in Wyoming! My mistake, however, led me to two wonderful blogs. One was about the benefits of practicing silence, entitled “Finding Solace in Silence” by Kerine W. on wittedroots.com. She writes: “There’s always been more to silence than we think. It hasn’t been obvious because we’ve villainized it. We’ve given it negative connotations of loneliness, isolation, and the illusion that we’ll be missing out on all the things around us. I think we too often associate silence with loneliness, but a void filled with noise is still empty. I believe silence is recuperation.”

In the second, entitled “Finding Solace in Solitude,” Zat Rana comments on upliftconnect.com: “When you surround yourself with moments of solitude and stillness, you become intimately familiar with your environment in a way that forced stimulation doesn’t allow.”

Sadly, the events transpiring in the world around us on this new moon challenge our faith and our hopes. We don’t have the luxury of such time in the wilderness when rockets give only seconds to find shelter. And ceasefires rarely yield the silences that bring about the reflection and reassessment required for true transformation.

Then again, maybe a few days off will give everyone a chance to take a long bike ride in the desert. It certainly worked for me.

Rabbi Craig Scheff

OJC Pride – Our Youth will Lead Us

As a rabbi, one of my favorite things is when our youth lead Shabbat services. The high school leaders take ownership of the evening; they daven with authority, encourage our religious school kids to participate, and always create and perform an engaging parasha play.

This past Friday, April 12, was all of that and more. In fact, it was a great deal more. Not only was it Youth Shabbat at OJC, but it was also the Day of Silence nationally, and our youth wove these two experiences into one very special evening.

Begun in 1996 at the University of Virginia, the Day of Silence is now observed at colleges and high schools across America to spread awareness about bullying and harassment of people in the LGBTQ community. Students and teachers vow to be silent for the day, showing solidarity for LGBTQ students who are too often silenced.

At services, our OJC kids gave out rainbow stickers, read poems and quotations to educate our congregation, and taught sign language for Sh’ma. One teen read a poem she wrote; in part it follows:

One day a year my silence speaks more than I ever could out loud.

My silence speaks for those who stop talking,

those who are forced to stop talking by a world that can’t accept them

for who they are or who they love.

After services, the brother of one of our congregants shared with me that he had never felt so accepted as a gay man and a religious Jew. He was overwhelmed by the feeling of welcome and comfort that he experienced. This man has been looking for a spiritual home for years. I thank our kids for leading the way in establishing OJC as safe space.

We grownups are doing our part as well. OJC is one of sixteen Conservative Jewish congregations across America in the third cohort being trained by United Synagogue and Keshet to be an inclusive, safe space for people who identify as LGBTQ. During Pride month (June), we are planning a Pride Shabbat (May 31 and June 1) and an inclusion and advocacy training with our Board of Trustees, Pride Committee, and professional staff.

Four of our Pride Committee members are teenagers. They lead the way for all of us, teaching us about what they accept as a natural part of their lives: God created all of us in God’s image. Some of us have brown hair, some are blonde. Some of us have blue eyes and some have green. Some of us are straight and some of us are gay. All of us deserve a seat in a sanctuary. That’s why it’s called a sanctuary.

Please let us know if you are interested in participating in OJC Pride. Contact our chairs, Sabina Tyler and Doug Stone at ojcpride@gmail.com.

And if you have questions about the LGBTQ community, ask a young person. They will be our teachers!

Heart in hand

The root of the Hebrew word for sacrifice, korban, can be translated as near or close. Sacrifice, then, is better understood in the biblical context as the way in which we draw near to the Divine. It is an invitation to achieve a sense of intimacy and communion with God. In our modern context, sacrifice is what we offer of ourselves in our attempt to achieve a deeper connection with those people, causes and things about which we are passionate.

Moreover, the fiery passion that may accompany intimacy, if unchecked, can be all-consuming, excluding to others, and costly to the self. When we care passionately about a person or a cause, we may throw ourselves–our emotional energy, our time, our resources–into the relationship. Sometimes we may even go too far in our zeal, forgetting about self-care and about our other priorities, and excluding the voices of others who may share our passions or who may stand in opposition because of their own hierarchy of values.

Relationship requires sacrifice. If we are to achieve true intimacy, we must be ready to give with no expectation of reward, to assume the risk of being hurt or even of hurting another despite our best intentions. We must be prepared to get messy, because the intensity and zeal that can accompany intimacy is not always accompanied by rational behavior.

But sacrifice also requires regulation and control. The failure to curb one’s enthusiasm can lead to disastrous results, harming the parties to the intimacy and those tangentially related. While we may no longer approach God with sacrifices in hand, we must build sanctuaries in our hearts, with altars fed by our purest intentions, upon which we offer our deeds. And as we bring our souls to the altar of intimate connections, may we not lose sight of those around us ready to do the same.

Rabbi Craig Scheff

Local Jews

It’s a cold Sunday morning in February, the time is 8:55am. Sitting by the window in our Daily Chapel, I have a good view of the synagogue driveway.

Unfortunately, there are no cars entering. From my spot, I can actually see two blocks down the main street that approaches the driveway. Not a car in sight.

And we have 8 people in the room.

And 2 of the 8 are saying Kaddish.

Just up from shiva for their loved ones, they have come to the synagogue on this morning to find solace in community, and I am afraid we are about to fail them.

I pick up my phone, open my texts, and call up my chat group “Local Jews.” These are the families with younger children who have moved into our synagogue neighborhood over the last few years. They walk to synagogue on Shabbat. They tailgate with Rabbi Hersh and his wife Loni in the parking lot after services when the weather is nice. Their children wait around for me to change my clothes and bring out the boxes of Good Humor eclairs. They share coupons to the food store in our text group, and debate whether hot dogs are sandwiches. They wish each other a Shabbat shalom.

I’ve never used this particular forum to seek support for the synagogue, so I hesitate. I don’t want my neighbors to feel that I don’t respect the boundaries between the social neighborly connection we share and the synagogue connection we have in common. I don’t want them to feel any sense of guilt if they must turn down a rabbi’s request.

But time is growing short. And the window of opportunity is closing. So I text:

“Good morning! Don’t usually (ever) do this, but there are a couple of people saying Kaddish this morning and we are 2 short of a minyan. Can anyone drop by for 15 minutes?”

I hold my breath.

Seconds later my phone buzzes: “Gives us a few minutes. Dragging kids from beds.”

Ten minutes later, mom and her two young teens walk into the room, smiles on their faces, siddurim in hand. Imagine that, I think to myself. Teenagers who have just rolled out of bed, leaning into and giggling at their mother’s side. On a Sunday morning at 9am.

The sight takes me back to my own youth, to the many Sunday mornings I spent sitting under my father‘s right arm, surrounded by people a generation (or two) ahead of me. I recall how they greeted me with warm smiles and expressions of appreciation for my presence. They made me feel seen. They made me feel important. They made me feel connected.

My guilt over crossing some imaginary boundary dissipates, as I remember why this family moved into the neighborhood in the first place, around the corner from the OJC. They chose to make the synagogue and its community a focal point of their lives. For their own benefit and for the benefit of others.

Do I wish that people would want to come to services on Sunday morning for a half hour without prompting? Of course I do. But I’ll take neighbors who eagerly answer the call when they are needed any day of the week. And I’ll always cherish that moment when a teen sees the look on the face of an adult, telling them they’ve made a difference in someone’s life.

Local Jews, I promise not to abuse the privilege of having you as neighbors. Unless you give me permission to do so!

Rayna and Zev, I see you. You are more important to us than you know. And while you may not be able to name the feeling now, I hope that someday you will look back and recognize the way connection to community was cultivated in your lives. Mom, great job.

Rabbi Craig Scheff

It’s the 9th of Adar! What are you doing about it?

It is the ninth of Adar Alef on the Jewish calendar. According to the Talmud, almost 2000 years ago on this date, two famous houses of study, Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai, became so entrenched in ideological battle over eighteen legal matters that they turned to violence. Tradition tells us that their destructive impulses led to the death of 3000 scholars and students all on one day. This tragic day was declared a fast day in the Shulchan Aruch, but it was never observed as one. Perhaps the joy associated with the month of Adar stifled the impulse to commemorate a day of shame and sorrow.

To me, this day represents something especially tragic as the disagreements between the Houses of Hillel and Shammai are most often taught as representative of constructive conflict, the ability to disagree with respect for one another’s viewpoints. What could have gone wrong? I imagine that one scholar or another in either or both of the study houses forgot to practice humility. This scholar or that one influenced his students by appealing to their egos, convincing them that arguments were made to be won. Soon the legal scholars no longer abided by the simple rules of a makhloket l’shem shamayim (disagreements for the sake of Heaven). They no longer could argue the issues while respecting their opponents, maintaining good relationships with them, and even admitting to being wrong sometimes. The inability to engage in constructive conflict led to violence as it does to this very day.

In 2013, the Pardes Center for Judaism and Conflict Resolution declared the ninth of Adar as the Jewish Day of Constructive Conflict. 9Adar Project

We are observing the ninth of Adar this year at Orangetown Jewish Center through a variety of educational opportunities. This past Shabbat, my 9Adar sermon was about civil discourse and the necessity to learn from multiple points of view. Rosh Hodesh Celebrations and OJSalon studied texts about constructive conflict and took pledges to participate on this day in a ta’anit dibbur, a “fast” from destructive speech. The Chafetz Chayim stated that if one chooses to fast for a spiritual purpose, it is far better to fast from speech than from food. We pledged to abstain from lashon hara, gossip. We have worked this past week to notice when we say things that are not truthful, positive, necessary, or kind. On this day, we commit to engaging either in positive speech or in silence.

Will you join us? Never before have the events of the ninth of Adar 2000 years ago felt more compelling and cautionary. In her book, From Enemy to Friend: Jewish Wisdom and the Pursuit of Peace, Rabbi Amy Eilberg offers ten suggestions for practicing the art of sacred disagreement. (You can read all of them here: 10 Ways to Practice Peace on the 9th of Adar) I offer just three here:

- Invite someone of another religion or political perspective to lunch.

- Call or email a friend or relative with whom you have felt tension, expressing a desire to reconnect.

- If someone speaks sharply or critically to you today, stop and ask yourself what pain or pressure in his or her life might have led to that moment of harsh speech.

If you try any of these techniques and are moved, continue the next day, and the day after. As Rabbi Eilberg encourages us, the health of our community and our world may depend upon it.

Says Rabbi Tarfon in Ethics of the Fathers, “It is not your responsibility to finish the work of perfecting the world, but you are not free to desist from it either.” Pirke Avot 2:21

Wishing you empathic, compassionate conversation on the 9th of Adar and all the days that follow,

Rabbi Paula Mack Drill

These are the Rules

Our grandfather, Israel Neiman, died the week the Ten Commandments were read in synagogue. Upon reflection and discussion as we find ourselves amidst the family’s observance of shiva, we realized that these mitzvot can offer important insights into the Jewish customs and traditions of mourning. As regular bloggers, and as brother and sister, we united our thoughts to co-author this week’s blog.

In the wake of loss, despite best intentions, many say and do the wrong things. This is true for those who want to comfort the mourners, as well as for mourners who receive the community that comes to pay its respects. Left to our own devices, we flounder in uncertainty and faux pas, the results of which cause anxiety and discomfort for all parties. During times of loss and grief, levels of anxiety and emotion are elevated; not a good time to “wing it” or propose constructive suggestions in the moment.

Time-tested traditions and mourning rituals are well-established to offer comfort and assurances to those who have suffered loss and are observing shiva. They also prescribe ways to receive expressions of sympathy and communal support without being overwhelmed, exhausted, resentful or burdened by the need to serve as host. These rules also benefit the community by enabling visitors to feel they truly bring comfort to the bereaved, even as they receive an opportunity for reflection and inspiration in turn.

In the spirit of the Ten Commandments, we offer these interpretations in the context of mourning:

1. “I am the Lord your God.” There is a God that created us with a breath. The death of our Zaydie is the return of that breath to God. We stand in awe of the notion that our grandfather’s soul has been returned to its source.

2. “You shall not create false images to bow down to them.” In the shiva home, mirrors are covered so we are not distracted from the deeper significance of the life that was lived. We are not meant to live in the physical world during the week of shiva. We tear our clothing to strip away the external; to live in limbo between the torn and the whole. Physical trappings—clothing, makeup and displays of materialism—are false images of existence that further separate us from the life of the soul we remember.

3. “You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain.” In remembering loved ones, the stories we share should not demean the memory of the person or disrespect the mourner. At times we feel the need to bring levity, but humorous stories at the expense of the deceased may be degrading and hurtful to a mourner.

4. “Remember the Sabbath to keep it holy.” The public observance of shiva is suspended on Shabbat, though private mourning continues. Even mourners need to breathe in the sanctity of the day. Shiva is exhausting; physically and emotionally draining. Mourners need to “re-soul” themselves just like everyone else.

5. “Honor your father and mother.” Parents anticipate the needs of their children. It is a rare opportunity to show honor by anticipating the physical and emotional needs of one’s parent during in mourning period.

6. “Don’t murder.” Families have complex dynamics. The intensity of emotions at a time of loss can give way to conflict. The week of shiva is not the time to act on impulses or unpack baggage.

7. “Don’t commit adultery.” Mourn the relationship you had with the person you lost. Do not “reinvent” it. Treat the relationship with honesty and integrity, even if it was not ideal. If the relationship was lacking, honor that story too; recognize the pain that accompanies lost time and lost opportunity.

8. “Don’t steal.” Grief in a shiva house belongs to the mourner. A visit is not the time to share your own stories or express your personal sense of loss; unless you are invited to do so.

9. “Don’t bear false witness.” Offering that you feel very blessed to have known the deceased is very different than telling the mourners how blessed or lucky they were. Don’t offer that you know how a mourner feels because of your own experiences. This is plain false.

10. “Don’t covet.” Saying Kaddish, as an example, belongs to the mourners. The loss is theirs, as is their obligation to mourn. While the community may stand with mourners as a sign of support, Kaddish is not to be recited with them. Only “Amen” is said to answer and affirm their prayers. Sadly and inevitably, we all will have our own times to mourn.

That being said, our modern sensibilities—often characterized by a sense of entitlement and a lack of empathy—require a redefined set of rules to correspond with a new reality. To this end, we offer ten helpful guidelines for the modern shiva house:

1. You shall designate a non-mourner family member or friend as your Shiva Coordinator. You need someone to take charge of the details and schedule from meals to minyan.

2. You shall set defined visitation hours. So that people won’t come too early or stay too late, consider two hours in the afternoon and two hours in the evening; leaving time for a nap. Carve out personal mealtime – for you and your family – and stick to it. That’s it. (And don’t forget to put out the chicken that needs reheating, at least forty-five minutes before you want to eat.)

3. You shall plan your own menus. Too much food causes too much stress. Notify friends of the schedule for meals. Specify that the food is for the number of mourners, plus four. If there are special food considerations (Kosher, gluten-free, nut-free, etc.), be specific and clear.

4. You shall affix a sign to the front door. It should read: “Please don’t knock or ring; come right in – but only between 2pm and 4pm or 6:30pm and 8:30pm. Otherwise, please wait outside or in your car. Or use your GPS to find the nearest coffee shop.”

5. You shall place a guest book by the entryway for visitors to sign in. This will remind you after shiva who came. But also, by the book, leave a sign that says: “Please find a seat facing the mourner. Limit your time to 15 minutes maximum. However, if others are waiting without seats, please limit your visit to 10 minutes.”

6. You shall sit on a chair and stay put. Sit in a spot that provides access to visitors and offers limited seating around you. Do not get up except to go to bathroom, bedroom or to stretch (all of which are important). Visitors will get the message and limit their time with you when others are standing by waiting for a seat. If you are hungry or thirsty, ask anyone to get you what you need.

7. You shall wear an amulet around your neck. It should say: “Please don’t hug or kiss me. I am immunosuppressed. And no one wants to see your behind or your cleavage as you bend over to comfort me.”

8. You shall shut off all ringers and ask others to do the same. People should not call a shiva house (except family). If you wish to reach a mourner and can’t make an in-person visit, send an email or a text to someone else in the household. The incessant noise is unnerving!

9. You shall not network. As a visitor, do not cultivate business opportunities or play Jewish geography upon visiting a house of mourning. The mourners wear a torn ribbon or article of clothing and sit on low benches (hopefully), so they can be identified easily. When visiting, make a bee-line for them, pay your respects, avoid side conversations, and depart.

10. You shall celebrate the life of your loved one as you choose…even if that means ignoring rules 1 through 9. But don’t forget, it is a long week and you can’t party like you used to. So pace yourself!

Mom, thanks for allowing us to take this opportunity to teach with a little humor. And we pray that you find comfort in celebrating Zaydie’s 100 years of life, 79 years of marriage, 9 grandchildren, 26 great-grandchildren and 4 great-great-grandchildren.

We love you very much,

Craig and Cheri

Marching Together, Alone

Most importantly, the fight against hatred, ignorance, oppression and marginalization has the potential to bring out the best in good people who share certain values. It is those shared values that enable them to overcome their other natural and nurtured differences, to march side by side, to learn from one another, to sympathize and empathize, to conquer biases and assumptions, to pursue shared goals despite approaching from different angles.

In advance of the 2017 Women’s March on Washington, organizer Vanessa Wruble, a Jewish journalist, invited Tamika Mallory and Carmen Perez (two activist women of color, for gun control and criminal justice reform, respectively) to be part of the leadership team that would organize the march. That first march, which was fueled by the response to the Election Day results, was a symbol of unity among women of all colors, the LGBTQ community, advocates of other social justice causes, and voices of progressive values in general.

In the wake of that first event, however, a rift developed within the leadership team. Mallory and Perez, along with Linda Sarsour (former executive director of the Arab American Association of New York), felt that Wruble could not be an effective leader of the march going forward given her status of white privilege and power, and that women of color would create a stronger coalition of voices from marginalized communities. At the same time, Wruble felt that she was a victim of anti-Semitism, being pushed out of the leadership because she was Jewish, and that the ties that Mallory, Perez and Sarsour had with pro-Palestinian causes, along with their connections to Louis Farrakhan, were strongly influencing the character of the coalitions they were seeking to establish.

Martin Luther King, Jr. seized upon the story of the Israelite journey from slavery to the Promised Land, which we read this weekend in synagogue, as a shared narrative between the Jewish and African American communities. He was vociferous in his support and admiration for the State of Israel. He did not marginalize the Jewish experience as one of privilege or power. “When people criticize Zionists they mean Jews, you are talking anti-Semitism,” he said, recognizing the tendency to label Israel advocates as oppressors. He saw the struggle for social and racial justice as a goal he shared with the Jewish leaders who marched at his side.

The rift within the Women’s March movement is, unfortunately, emblematic of the deteriorating state of relations between the Jewish non-Orthodox community and the larger progressive community.

As a rabbi and community leader, I have advocated for certain causes side by side and shoulder to shoulder with communal leaders who have shared my passion for those particular causes, though we may have stood opposite one another over other issues. I could overlook our differences, sometimes as admittedly with great difficulty and discomfort, for the sake of our shared goals and alliance in faith. I felt that sense of common purpose yesterday, sitting in a Nyack church, listening as pastors recited words of Torah.

There comes a point, however, where I cannot ally with those who subscribe to the opinions of haters. Holocaust deniers, conspiracy theorists and other dehumanizing anti-Semites, and those who offer a platform for their views, are beyond partnership. Marching side by side with disseminators of hate would be a denial of my identity, and an insult to those I consider my constituents and to the legacy of Dr. King, no matter the cause.

I will continue to work for change from within, to influence opinions from a place of engagement. But when social justice leaders and organizers succumb to ignorance and hate, forgetting the human dignity inherent in each of us beyond the narrow labels that may be assigned to us, I will choose to march separate and apart. And, if necessary, alone.

Healthy Body, Healthy Soul

It is that date on our calendars, December 31. If you are like most people on New Year’s Eve, you will be setting resolutions before the ball drops in Times Square.

Many of those resolutions will be some version of being more healthy. We pledge to start a new exercise regimen, eat a healthier diet, relax more, etc.

And if you are like 80% of people, by February you will no longer be meeting your goals.

I suggest that health and wellness are more achievable as a way of life rather than as a goal to be achieved in the first weeks of January. One of my yoga teachers encourages us to see changing our patterns as a curious experiment. She says that it is more effective to be gentle with ourselves and take several small actions in the direction we want to go rather than setting impossible long-term goals.

“Fine and good,” you say. “But what are these sentiments doing in my rabbi’s blog post?”

I’m glad you asked!

Jewish tradition teaches that our body is the Temple of our Soul. God created each one of us in God’s image; therefore, our body is part of our sacred being, the place where our Godly spark resides. As Rabbi Simon Jacobson has written Read More…

Recent Comments