One tree

They wanted to tear down the tulip tree, our neighbors, last year. It throws a/ shadow over their vegetable patch, the only tree in our backyard. We said no./ Now they’ve hired someone to chainsaw an arm—the crux on our side of/ the fence—and my wife, in tousled hair and morning sweat, marches to stop the/ carnage, mid-limb. It reminds her of her childhood home, a shady place to hide./ She recites her litany of no, returns. Minutes later, the neighbors emerge. The/ worker points to our unblinded window. I want to say, it’s not me, slide out of/ view behind a wall of cupboards, ominous breakfast table, steam of tea, our two/ young daughters now alone. I want no trouble. Must I/ fight for my wife’s desire/ for yellow blooms when my neighbors’ tomatoes will stunt and blight in shade?/ Always the same story: two people, one tree, not enough land or light or love./ Like the baby brought to Solomon, someone must give. Dear neighbor, it’s not/ me. Bloom-shadowed, light-deprived, they/ lower the chainsaw again.

The poem, One Tree by Philip Metres, is about conflict at the local level. The struggle is neighbor against neighbor and the battlefield is the back yard. The fence that separates properties cannot keep out the tree’s shade cast from one lot into the next. The conflict, however, is not a two-sided affair. The narrator-husband is a bystander who is sympathetic to both claims. The worker is a combatant by proxy, a participant without an expressed conviction. The poem reminds us that while the sides to any confrontation might be seen from the outside as monolithic, divisions within the opponents might, and invariably do, exist. And unwitting players are bound to get caught in the conflict as well.

The rivalry between Jacob and Esau as described in this week’s parsha, Toledot (Genesis 25:19 – 28:9), begins in Rebecca’s pregnant belly. Their conflict is founded in their nature and fed by their nurture. Their methods and their goals couldn’t be more divergent. And their struggle is intensified by the fact that they are family. Neighbors may disengage or move. Siblings remain enmeshed by a shared history, a common bond of blood, and a character dynamic that replays (perhaps subconsciously if not overtly) at every encounter. While the men may grow like branches in opposite directions, they remain attached to the same tree.

In a 2010 interview with Krista Tippett on the podcast On Being, Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, former chief rabbi of the British Commonwealth who passed away on November 7, discussed the dynamics of political and religious conflict. In addressing conflict between faiths, he offered the following: “We all come from a single source. Everything that lives has its genetic code written in the same alphabet. Unity creates diversity. So don’t think of one God, one truth, one way. Think of one God creating this extraordinary number of ways, the 6,800 languages that are actually spoken. Don’t think there’s only one language within which we can speak to God.”

How much more does this teaching apply to us as a human family? Our diversity–of ideologies, of political philosophies, of beliefs, of values, of behavioral patterns–can be traced back to the same singular source. When we ignore how interconnected we are, we “throw shade” across our fences, depriving one another of light and the accompanying growth, and we fail to see ourselves in the other. In recognizing our shared code, we can find common ground between siblings, neighbors and ideologies. In understanding how nature and nurture have shaped the many permutations of that code, we can begin to understand and appreciate the diversity and uniqueness of every human family member.

In the ongoing struggle for recognition, for love, for resources, for power, we might make the same mistake as the poem’s narrator. “It’s not me,” they wish their neighbor would know. But, of course, it is me. And it is you. The tree is ours; it is us, our history, our heritage and our responsibility. But it is not ours alone. It belongs as well to our siblings, cousins and neighbors. It belongs to our friends across the aisle and across the oceans. The tree is ours.

In memory of Ruth Ignatoff z”l, mother of Jonathan Drill and his four unique and loving siblings,

Rabbi Craig Scheff

You don’t know me

Thank you to the hundreds who showed up for Shabbat this past weekend to hear our message, and to know and to love one another a little better. The following is the message I shared:

You don’t know me.

As I stand here on this Shabbat morning welcoming those who have come to celebrate with our Bar Mitzvah and his family, those who chose to show up for Shabbat with their synagogue community, and those who have come from our neighborhood or larger community, Jewish or not, in order to pledge solidarity and unity in the face of hatred, I realize you probably don’t know me. Not the way I’d like you to.

If you did, you’d know that last Saturday, while I was reading a story in my synagogue about my ancestor Abraham—how he welcomed strangers into his tent, providing them food and shelter from the heat of the day—eleven members of my extended Jewish family were being executed for no reason other than that they were Jewish, and that they were learning the value of welcoming the stranger.

You don’t know me.

If you did, you’d know that while I was learning this week about my ancestor Abraham and how he purchased a burial place for his wife Sarah, how he saw himself as a stranger amongst his neighbors and thus insisted on paying the full price for his plot so no one would ever question the legitimacy of his presence in their midst, my extended family was burying its dead, suddenly feeling very much like strangers themselves and, by extension, shaking my own sense of belonging.

You don’t know me.

If you did, you’d know the pain I feel as a result of having been offered more wishes of congratulations on my favorite baseball team’s victory than wishes of condolence on my sense of personal loss because of the murders in Pittsburgh.

You don’t know me.

If you did, you’d know that in the week ahead I’d be commemorating the 80th anniversary of Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, a night that signaled the start of the Holocaust, sending my grandparents into flight from their home in Poland, to Russia where my mother would be born in a labor camp, then to a displaced person camp in Germany, and finally to the shores of these United States.

You don’t know me.

If you did, you’d know that this past week I made a donation to HIAS (the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), the same organization that my fellow Pittsburgh community supported, because I too believe in protecting refugees, and because without its support my family would not be here today.

You don’t know me.

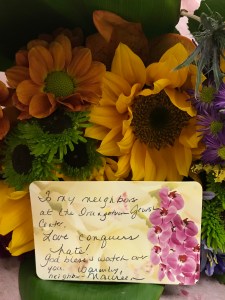

If you did, you’d know that this past Tuesday Rabbi Drill and I took our sixth and seventh grade students around our OJC neighborhood to extend personal invitations to our 35 neighboring homes to join us this Shabbat in solidarity, and again on our Mitzvah Day in two weeks for breakfast, just to know one another and share in doing some good.

You don’t know me.

If you did, you’d know that when I was growing up here in this community, I knew my neighbors by name, but my children have grown up in this neighborhood not knowing the people who lived across the street.

Winter is coming. (Yes, I am a fan of Game of Thrones.) And while this winter may not be ushering in the ultimate battle between the forces of good and evil, I do believe we are on a dangerous path. When I was a child, winter meant shoveling my own driveway and going to my neighbors with a friend to ask if they wanted their driveways cleared or their cars cleaned off. Today, winter means locking your doors, lowering your shades and communicating with a friend virtually.

I do not believe that we find ourselves today in the winter of 1938 Nazi Germany. Most importantly, the police and the law are here to stand with us and to protect us, as they have been throughout this week. Our Town Supervisor and neighbor Chris Day is with us today to assert that an act of hatred against one of us is an act of hatred against us all. Our sisters from the Dominican Convent in Sparkill are here with us to share our pain and our mission in combating violent acts of hate with loving acts of kindness. Our Rockland Human Rights Commissioner Constance Frazier is with us today to share our outrage and determination not to let our community be home to those who target the weak, the aged, the young, those of a particular religion, gender, race, sexual identity or political persuasion.

If you don’t know me by now, I bear partial responsibility for not knowing you, for not introducing myself and giving you the chance to know me and what I value.

If you don’t know me by now, let me share with you that my faith commands me to love my neighbor and my tradition teaches me that I cannot love whom I do not know. In the days ahead may we come to know one another, so that our love for one another and for our neighborhoods, communities and country will truly come to be stronger than the hatred that seeks to tear us apart.

I can go to the polls this Tuesday and vote according to my values and who I am, but that is not going to change my relationship with you. And so I beg of you—as we leave here today and as we head to the polls in the week ahead to elect those with the power to shape our communities on a policy level—to knock on a neighbor’s door this week, to make an introduction, to maybe even extend an invitation, so that we may know one another again.

Recent Comments